A slice of art, history and archeology from the banks of the Ganga and the Uttari Non in Kanpur

Exploring the sites of Nonha Narsinghpur, Radhan and Lala Bhagat

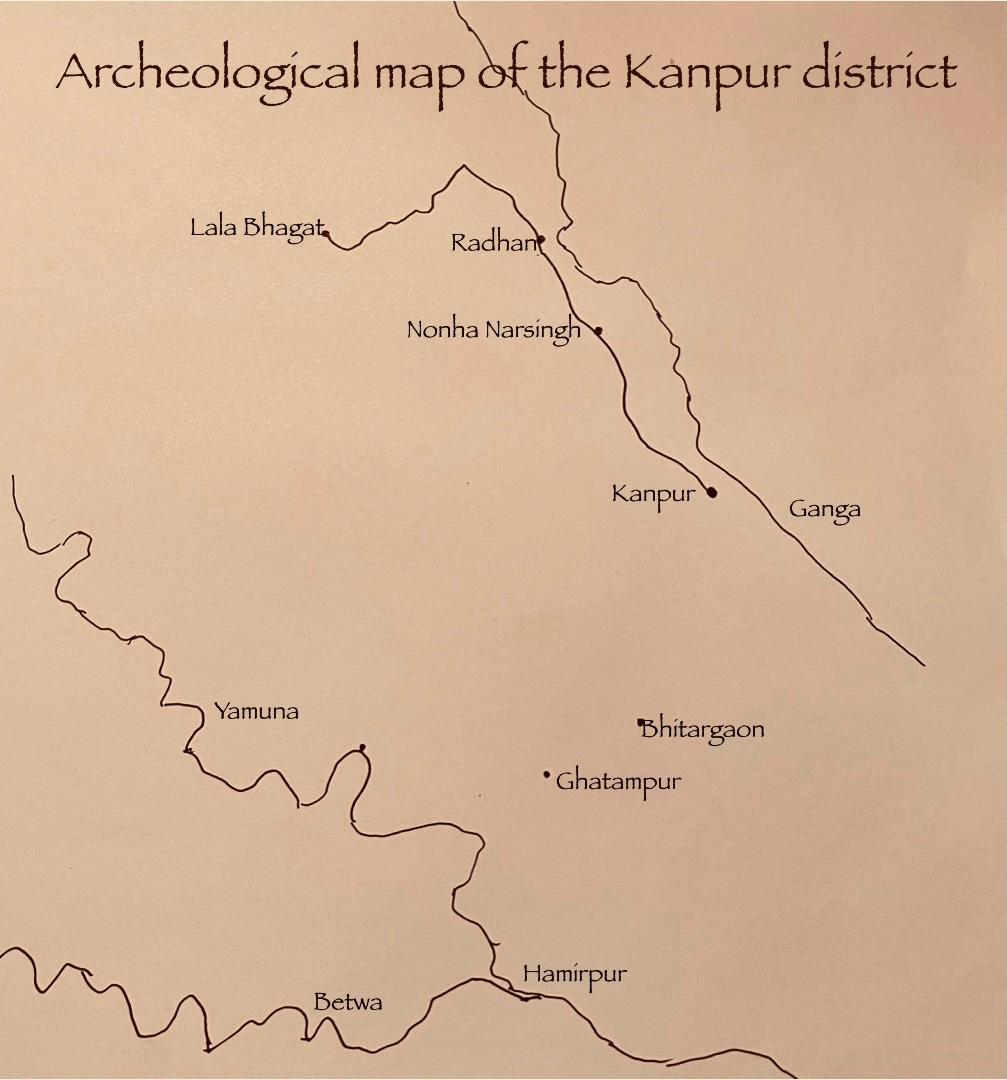

In this short essay we will take a tour of three ancient sites of Kanpur which dot the banks of the Ganga, and the river Uttari Non. Two of these sites, namely Nonha Narsinghpur and Radhan, are those whose cultural beginnings can be traced from as early as the Copper Age. Lala Bhagat is the site which would, in the ancient times, been an important religious centre of the Ganga valley connected with the worship of Surya and Kartikeya, among others. These sites are within an hour’s drive from Kanpur, and if carefully developed, they can grace the tourist map of the region besides contributing to the educational corpus on the civilisational roots of this part of the land.

An archaeological and a historical perspective on the region surveyed

Between the period 2500 BCE to 800 BCE large scale settlements dotted the Ganga plains. From the Harappan settlements to the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture which was contemporaneous with the Harappan culture, the Ganga plains were thriving with human activity from a very early period with its rivers being the most preferred sites for building homes and earning a livelihood. Although a mostly riverine culture, settlements of the OCP period have also been found away from the rivers, around the lakes etc.

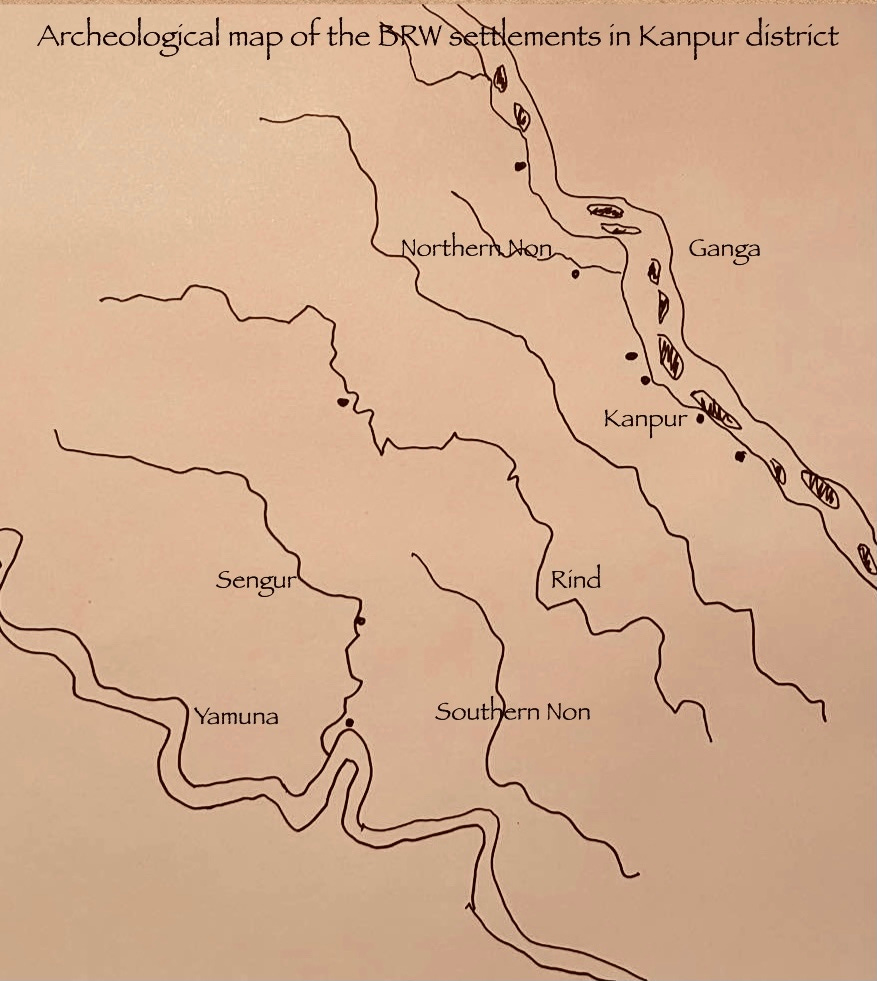

Another significant culture which developed in the Ganga plains was that of the Black and Red Ware (BRW). The Black and Red Ware is one of the earliest forms of ceramics to have been unearthed in the Indian subcontinent namely from the archaeological site of Lahuradewa from the Neolithic layer of its cultural deposits. Like the OCP culture the Black and Red Ware culture of the Ganga plains is also associated with the Vedic era which is identified with the Bronze and the Copper Age in its earlier part and the Iron Age in its later part. Scholars have attempted to trace the origins of this ware in archaeological cultures on the basis of its distribution pattern across various sites. Some have attributed it to the Harappans (Lothal), while others have linked it with the Ahar culture. It has also been advocated that the ware has Neolithic origins.

“The size of settlement during this (BRW) period on the Ganga was as big as 8 hect. while on the tributaries it was 2-3 hectares. When a settlement on the tributary reached to a size of 2-3 hect. (400-600 population) there was a tendency towards fission. They could not grow bigger in size as the settlements on the Ganga. The fission of settlements on the tributaries was due to non availability of sufficient good agricultural land in the vicinity of settlements. Further the soil along the tributaries was not as fertile as on the Ganga and this would have demanded a longer fallow period for the soils to regain fertility. Smith explains that settlements of long fallow cultivation tend to be small though the total population in the region may be large. The presence of large nucleated settlements on the Ganga is probably due to greater availability of good cultivable land and shorter fallow period”

“The size of nearly 80% settlements remained at the level of small village having population of 500. Only 20% of the settlements were large enough to accommodate a population between 500-1000. During the period only a few sites like Hulas, Atranjikhera, Radhan and Kaushambi had grown to size of nearly 2000 population or even more. The average spacing of settlements during this period was between 13 - 8 kms.”

Makhan Lal

The Painted Grey Ware culture of the Iron Age has been found to coexist with the antecedent Copper Age / Chalcolithic culture of the Black and Red Ware and Black Slipped Ware in nearly the entire Ganga plains from where these ceramics have been unearthed.

“The Braj region for sure presents the most dense settlement pattern in the entire subcontinent and the area west of Yamuna has to be the core area of the PGW where the minimum area required for the presence of a PGW settlement comes out to be just about 16 sq km. Tehsils of Chhata, Mathura, Sadar and Mant in district Mathura and Deeg and Kumher in Bharatpur district are very dense in PGW settlements and in district Hathras there is an alignment from near Sasni up to Hathras which has high concentration of PGW sites. But in areas of district Bharatpur where the distance is more than 40 kms from Mathura city and the soil is comparatively less fertile because of changing topographical conditions the concentration of sites declines considerably but still that might be at par with other areas of doab region which have high concentration of PGW sites. Now we have quite solid grounds to speak about the authors of the PGW culture. The PGW using people were indigenous to the area where their settlements are found in high density, i.e. the Braj region. They did not come from outside. Their pottery technology seems to be an advancement over the existing…so they were in continuity of the earlier folks…”

Vinay Kumar Gupta and B. R. Mani

Archaeological explorations in the Ganga Yamuna doab have brought to light in detail the pattern of settlement and movement of people during this NBPW and the early historical period.

“..the settlements extended beyond the range of locations of the previous times. A substantial number of settlements are now found away from the rivers and lakes. The increasing pressure on the soils along the river banks and the lake shores must have been one of the factors in the movement of people to new locations. Now the settlements are found not only in the areas less favoured in the earlier period but also in comparatively less hospitable areas” primarily due to technological advancements and administrative patronage.

“The tendency towards the splitting of settlements along the tributaries continued. The size of settlements rarely reached 4-5 hect in size…in general the settlement size increased and sometimes the size was as big as 15-20 hect. The average spacing between the two settlements during this period was 7-9 kms.”

Makhan Lal

Nonha Narsinghpur

Situated amidst the lush farmlands which form a recurring feature of the Ganga valley, and drained by the rivers Ganga and its tributary the Uttari Non (Northern Non) the ancient village of Nonha Narsinghpur in the Chaubepur block lies at a distance of twenty four kilometres from the district headquarters at Kanpur. Nonha Narsinghpur is the site of a huge archaeological mound which falls on the right bank of the river Uttari Non and is the place of discovery of an important stone inscription dated to the Pratihara era.

The archaeological mound of Nonha Narsinghpur is divided into the northern and the southern parts by the channels of the Uttari Non. Surface antiquities in the form of ceramics from the Painted Grey Ware, Northern Black Polished Ware, Shunga, Kushan, Gupta eras to as late as the early medieval period have been found strewn across the fields during explorations. Burnt bricks in varying sizes too have come to light indicating the possibility that there once existed a large town at the site which is now concealed by the mound. Several stone sculptures dated to the early medieval period have also been found at the site suggesting the place was inhabited and thriving till as late as the early medieval period. The condition of the badly mutilated sculptures hints that the settlement came under attack by the barbarians during the period of invasions. The waves of iconoclasm which gripped the Ganga plains left no place unspared from sustained religious persecution. The temple at the site although no longer standing still has its foundation intact which can give a fair idea of how it may have once appeared. There’s a Shivalinga in polished stone stationed on the southern mound. It’s believed the Shivalinga once graced the temple at the place which was razed to the ground during the medieval age. A panel depicting Mahishasuramardini dating to either the classical period or early medieval era is enshrined in a newly constructed temple at the site on the northern mound.

“The inscription lies on the ground near the Shivalingam on the southern mound which is locally known as the Nonha Narsinghpur mound. The inscription is incised on a carefully smoothened upper surface of a stone slab.. This inscription of 13 lines is only a fragment of an apparently large inscription. Not a single line of the inscription is intact, and almost all the extant lines are partially broken. The characters are Nagari of about ninth-tenth century AD. The language is Sanskrit and what remains in the inscription is in verse.”

Jai Narain and Bimal Chandra Shukla

The inscription which is of thirteen extant lines mentions the name of Bhojadeva the greatest ruler of the Pratihara dynasty of Kanyakubja. It mentions a Padmanabha muni. It records the grants of land made by a person named Shubhaditya to the Brahmins of the village which once thrived at Nonha Narsinghpur.

At present, the massive Shivalinga dating to ancient times is enshrined in a Shiva temple which is known as the Noneshwar Mahadeva temple. It’s situated in the middle of pristine agricultural fields in a neat layout with impeccable maintenance.

Radhan

Given the historical and cultural frame in the opening part of this essay we now take a short tour of the precious site of Radhan.

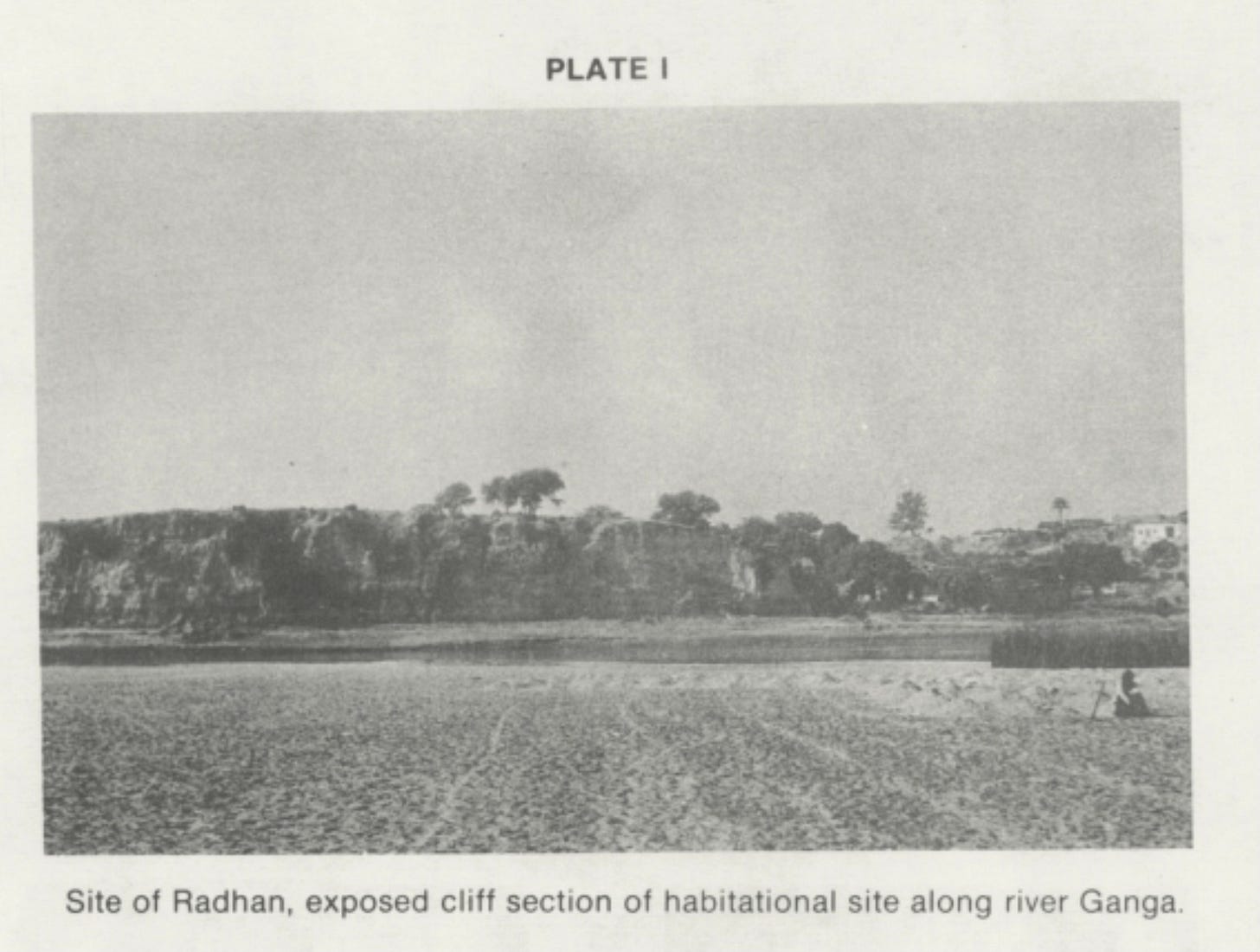

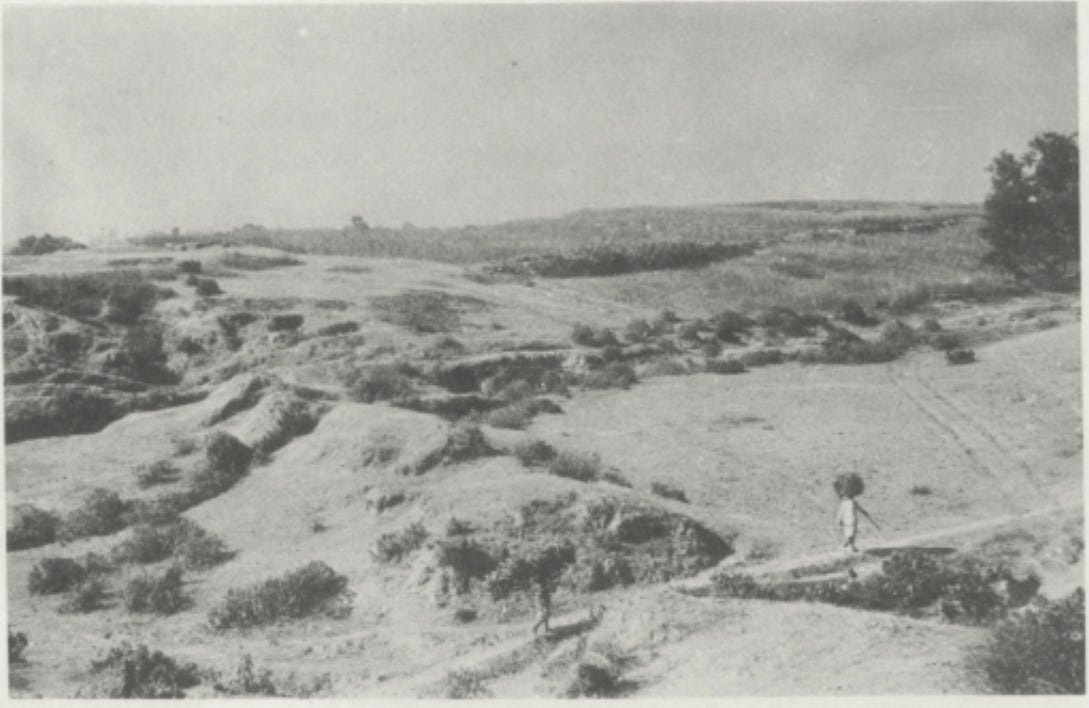

Situated on the right bank of the Ganga, around forty five kilometres from the district headquarters at Kanpur is the archaeological site of Radhan, in tehsil Bilhaur. The mound, lofty in size, and flanked by the river, houses much of the village of Radhan. Much of the western portion of the mound has been washed away by the river’s flow giving a glimpse of the mound’s profile. Seeing the scale of the site, it’s natural to assume that once upon a time an ancient and an important town thrived at this place.

Radhan is one of the sites in district Kanpur from which sherds of the Ochre Coloured Pottery were first discovered which put the place on the list of those significant sites which date to the Vedic era.

“The cultural period as could be delineated on the basis of pottery occurrences were BRW, PGW, NBPW, Red Slipped Ware to medieval period. The mound shows the remains of almost all the periods right from BRW period to present. This is one of the rarest sites where expansion has been horizontal rather than vertical.”

Of the three trenches that were dug natural soil could be reached only in one. The cultural deposits of this trench are as follows

- disturbed due to modern pits and robbing of bricks.

- NBPW deposit with structures of burnt bricks

- NBPW deposit without any burnt brick structures etc

- Uneven surface containing sherds of NBPW, PGW, OCP

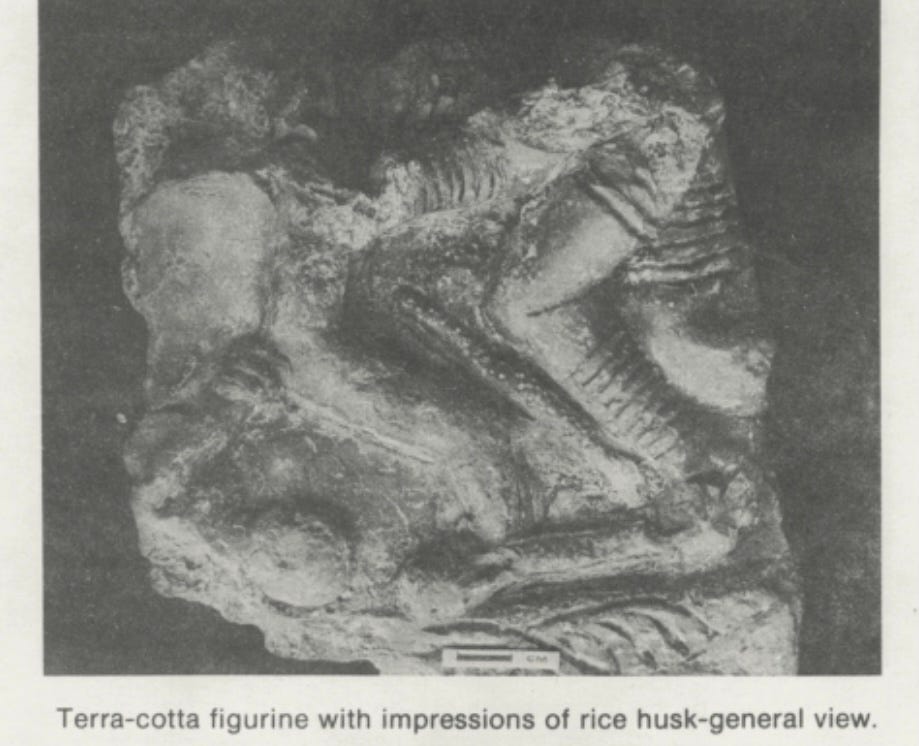

“During the course of excavations two structures of burnt bricks of Mauryan period…were found…One of the structures was worn out floor of bricks with foundation wall. The founding wall was of 14 courses and was built in brickbats pounded surface. The other structure was a brick wall of 15 courses. It seems that partly this wall was robbed. The finds include beads of carnelian, agate, jasper, quartz, copper and terracotta. A few rings of copper were also found. Points of bone, iron and copper were found in large numbers. Two highly polished circular weights of quartz and carnelian were also found among the iron implements the find includes two sichels, one hae, several knives, nails and fish hooks. Three triangular pieces of terracotta objects cut out of circular discs in perfect four parts. Six copper punch marked coins were also found.”

Lala Bhagat

“Among the various gods and goddesses who find representation on early Indian coins, Kartikeya occupies an important place. In early literature he is variously known as Kumara, Skanda, Karttikeya, Mahasena etc. The Vedic divinities represented in the form of Vedic symbols in art also include Kumara, who is described as the miraculous babe, the wonderful hero, the leader of the divine army and son of Agni. He also symbolises the principle of prana or life..

Patanjali mentions Skanda and Visakha as laukikadevata…From his comment on an important sutra of Panini it is clear that images of Siva, Skanda and Visakha were made for worship during his time (sampratipujartha).”

U. Thakur

Lala Bhagat is a small village in the Rasulabad block of Kanpur district. The village is the site of an ancient temple and the place of find of several religious relics dating primarily to the Kushan era. Among the finds is an ornately carved stone pillar which throws valuable light on the religious landscape of the place as prevalent during ancient times. The site has been described as a Buddhist site by some scholars, but the stone pillar showcasing the iconography of Sun, Lakshmi, and the cock capital (associated with Kartikeya) tells us this was a Hindu place of worship. The pillar dating to the Kushan era was erected within a religious complex as a mark of devotion to Kartikeya whose worship was hugely popular in this part of the region during the time as is evident from the many sculptural remains that have come to light from this part of the country. That sun worship formed an important part of the religious life of the people of those times is suggested by the many sculptures which have been discovered and the artistic traditions which evolved around the iconography of Surya which these sculptures give us a glimpse of. Kartikeya shrines of the Kushan era prominently incorporated Surya worship as seen at this site.

The connection between the Sun and Agni is also referred to in the Vedic literature.

"As envoy of Vivasvān Mātariśvan brought Agni Vaiśvānara hither from far away."

Rig Veda 6.8.4

To delve into what the iconography of the stone pillar of Lala Bhagat implies we take a look at some excerpts.

The stone pillar, besides a dancing peacock depicts “sunrise, the solar deity in his chariot preceded by Valakhilyas, dispelling darkness and creating joy, lotus pond with flowers in bloom and elephant pulling a lotus stalk. Lakshmi standing amidst lotuses bathed by elephants”

Such an elaborate depiction of Sun in what was a pillar dedicated to Kartikeya has had many scholars point to the association of the solar cult which has been prevalent in the northern religious landscape since very early with the worship of Kartikeya.

If we delve into the reasons for such an association we find many accounts from our sacred literature which

“The usual characteristic weapon of Subrahmanya is the sakti; the Markandeya Purana gives a short account of the origin of this weapon thus: Surya (sun) was once so powerful that his heat was causing damage to this world. Vishvakarman the celestial mechanic contrived to abstract a portion of the solar glory and rendered him innocuous. From the power taken away from Surya Vishvakarman fashioned the saktyayudha for Subrahmanya. It is worth pointing that the portion of the solar glory was transferred to Subrahmanya who according to Bhavishya Purana took his seat near Surya when the daityas attacked and when the gods rallied round him for his support. The same Purana informs us that the dvarapalakas of Subrahmanya are Surya…and…Siva. These facts coupled with the information regarding the origin of Subrahmanya distinctly point to its origin to the Sun…”

“Agni was invoked by the rishis for receiving the oblations in their yajna and that he descended from the sun; the Mahabharata states that on the day the rishis began their yajna the sun and the moon were together that is the day was a new moon day beginning from the pratipada day the seed of Agni was gathered for six days and on the shashthi tithi Subrahmanya of the colour of the rising sun came into existence. His davarapalakas are Surya and Siva (who is same as Agni or Rudra)…his six heads perhaps represent the six ritus or seasons, the twelve arms, the twelve months; the kukkuta of the fowl the harbinger of the rising sun and the peacock whose feathers display a marvellous blending of all colours represents the luminous glory of the sun; the saktyayudha is also of solar origin.”

T. A. Gopinath Rao

C. Sivaramamurti writes on the Lala Bhagat pillar in the Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India

“ A very significant early pillar from Lala Bhagat discovered and described by Pandit M. S. Vats shows the same aspect of padmini and her bloom in the morning when awakened by the sun is clearly suggested by a graphic portrayal of the sun in his chariot accompanied by two attendants, one holding a parasol and another a fly-whisk. As usual in early sculpture four horses draw his chariot, beneath which a demoniac head is represented to signify darkness dispelled. The chariot is preceded by three ladies representing Usha, Pratyusha and Chhaya. A number of dwarfish figures preceding the queens of Surya are the Valakhilyas who lead the chariot of Surya and who by their peaceful mien, and the sun by his effulgence, made Kalidasa choose this situation as appropriate for comparison with a similar scene of Satrughana in chariot being led on towards Mathura by thr Rishis, who suffered from the depredations of the demon Lavasa also of the nature of tamisra or gloom - very appropriate comparison as the sun dispels darkness :

आदिष्टवर्त्मा मुनिभिः स गच्छंस्तपतां वरः ।

विरराज रथपृष्ठैर्वालखिल्यैरिवांशुमान् । । १५.१० । ।

Raghu, XV.10

Beneath is the dance of the peacock with its tail opened wide in gay colours and suggesting the line hasishyati chakravalam. The elephant beneath it pulling up lotuses suggests the line : ha hanta hanta nalinim gaja ujjhara. But when taken as a whole all the figures exactly connote and act as effective commentary on the verse :

रात्रिर्गमिष्यति भविष्यति सुप्रभातं

भास्वानुदेष्यति हसिष्यति पङक्जश्रीः

इत्थं विचिन्तयति कोशगते द्विरेफे

हा हन्त हन्त नलिनीं गज उज्जहार

Kuvalayananda

the line bhasvanudeshyati hasishyati pankajasrih is more clearly set forth in this representation of the heralding of day break by swans flying in the air, the rising sun in his chariot, the joy of the lady of the lotuses suggested by the dance of the peacock signifying joy and the lady of the lotus herself down below, and finally the elephant pulling up the lotus stalks completing the sense of the verse. Even the cock shown on a pillar beside the lady of the lotus pond is a herald of dawn, and this is one of the finest representations personifying abstract thought like dawn or twilight or the charm of the lotus pond.”

References

Stone Inscription of Nonha Narsinghpur, Kanpur, U.P by Jai Narain and Bimal Chandra Shukla

Solar Iconography of Mathura by Suresh Pandey

Kārttikeya in Literature, Art and Coins Upendra Thakur East and West Vol. 24

Elements of Hindu Iconography by T. A. Gopinath Rao

Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India

The Development and Dispersal of Agricultural Settlements in the Ganga Yamuna Doab by Makhan Lal

Painted Grey Ware Culture: Changing Perspectives by Vinay Kumar Gupta and B. R. Mani